Click the audio player above to hear the podcast or read the transcript below.

TRANSCRIPT

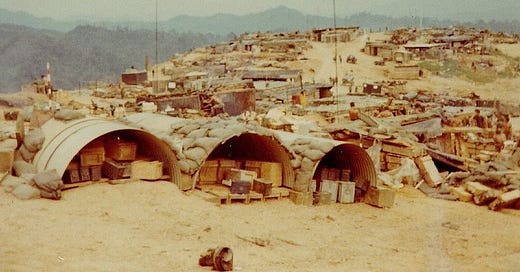

Mary Ann was a small military facility on a hill in a remote part of South Vietnam.

I don’t know who gave it the name Mary Ann, but it was a firebase that supported infantry troops on the ground in nearby areas.

During my time in Vietnam I served on several firebases with the 3/82 Artillery — Mary Ann, Crest, Baldy, Casey Jones, and Deja Vu. At least those were the names we gave them. The Army often referred to each of them as an LZ (Landing Zone) or just a number (something like Hill 191).

I wanted to begin this episode with Firebase Mary Ann because it holds a special place in my memory. Not for what happened while I was there but for what happened shortly after my unit left the hill and moved on to other firebases.

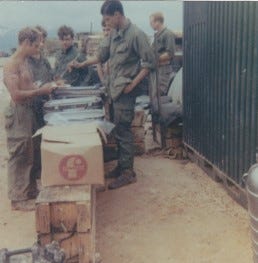

Photograph of Firebase Mary Ann from “Together We Served” (httpsblog.togetherweserved.com20211124fire-base-mary-ann)

On March 28, 1971, Firebase Mary Ann was attacked1 by VC sappers who crawled through the defensive wires and launched an attack on the 231 Americans and 21 South Vietnamese soldiers who occupied the base.

In the hour long battle, 33 were killed and 83 were wounded.2

It was a reminder that even in the relative safety of a firebase, this was a war and we all had to be prepared for what might happen at any moment.

THE JOB ON A FIREBASE

Our job on a firebase was to support the infantry units in the field. The 105mm cannons in my unit had a range of about 7 miles so we seldom saw the actual fights in the field between our units and the enemy.

Instead we relied on radio communications for what was happening on the ground and what was needed from us.

A FIRE MISSION

We always had someone at the radio in order to receive a call from a unit in the field.

If an infantry unit requested a “fire mission” the Forward Observer who was in the field would give us the grid coordinates and one member of our FDC team entered those coordinates into the computer. The computer, which we called Freddie, generated a shooting solution and another member of our team did a manual verification of the shooting solution with the help of a large topographical map.

When both agreed, the shooting solution was sent to the gun crews who quickly aimed, loaded the guns, and fired.

Usually our first shot was a “marking round” — a white phosphorus shell that exploded in the air above where the rest of the shells would shortly land.

The Forward Observer would give us corrections, telling us if we were long or short, left or right of the target, and we would make the necessary adjustments and send the corrected shooting solution to the gun crews.

Depending on the situation, the infantry could tell us either to “fire for effect” or to fire another marking round.

We would continue firing as long as the infantry needed our support.

If the soldiers in the field called in a “contact fire mission” it meant they were engaged in a shooting battle with the enemy forces and sometimes they would skip the marking round and request “fire for effect” right away.

We knew it could be a life and death situation for the infantry so we got very good at responding quickly and accurately in order to support them.

THE FIREBASE

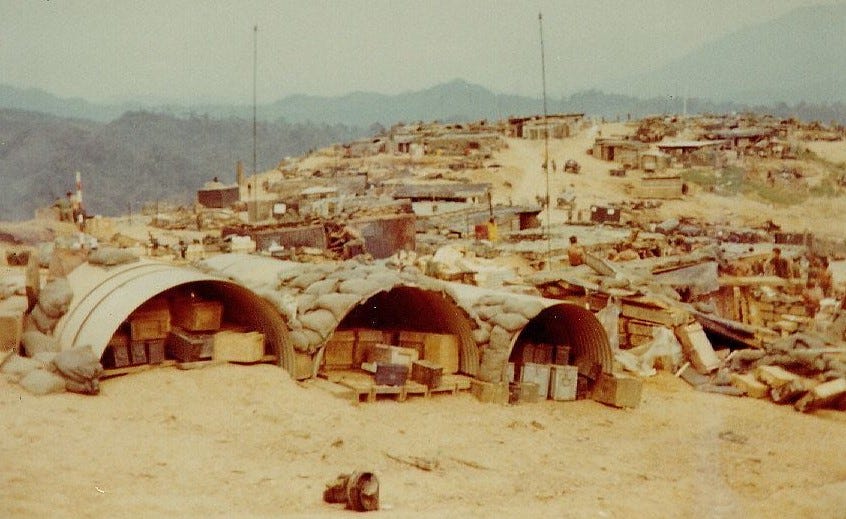

A chopper took me to the firebase where I would be working and dropped me off in my new world. I was introduced to the Fire Direction Control (FDC) team and given a bunk — actually a cot underneath a culvert half.

And, yes, Gunner was a part of our team. He was a good guy and he didn’t shoot any bugs out on the firebases.

THE ROUTINE

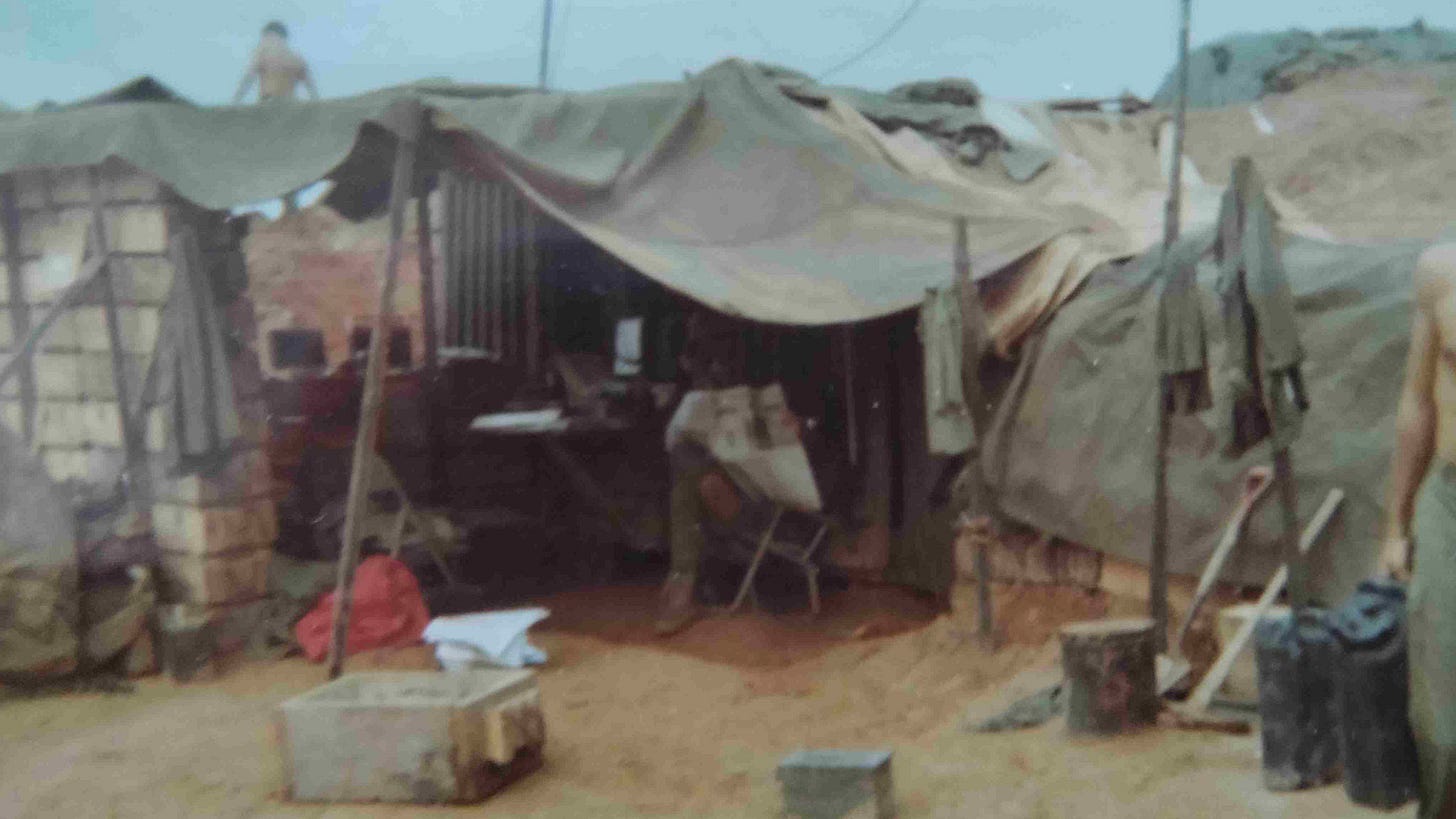

In our FDC we usually worked 12 hour shifts — switching at noon and midnight — seven days a week. Someone was always awake at the radio in case a fire mission was called in.

One of the noticeable elements of the FDC center is that it had lots of antennas. We needed them for our radio communications but we also knew it made our location a prime target if the base were to come under attack.

Our Fire Direction Control (FDC) unit on LZ Baldy. From my personal photos. Not the most spacious of accommodations but it gave us room to do our job.

FOOD AND WATER

Food and water are important items for soldiers and on these remote firebases. There weren’t any spigots to turn on for water or any stores to go to for food. So they had to bring everything to the troops.

I arrived at LZ Crest by chopper. Our FDC center was in the upper left of this photo. Popping smoke was a security action to let the chopper pilots know it was safe to land. (My photo.)

Here’s a Marine helicopter — we called it the Jolly Green Giant — bringing some potable water to LZ Casey Jones. (My photo.)

It was always nice when there was a hot meal.

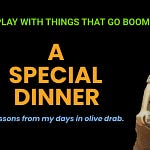

A hot meal is served on LZ Crest. This was the chow line. (My photo.)

And when hot food wasn’t available, there were always C Rations.

A couple of members of my FDC unit sitting on breakfast, lunch, dinner, breakfast, lunch … well, I think you get the idea. Inside those boxes were cans of food designed to provide us complete meals. Some of the meals were even edible. (My photo on LZ Casey Jones.)

THE LATRINE

I apologize for talking about latrines, but I have to admit that on my first firebase, the latrine was a very memorable part of my experience in Vietnam.

You should know there was an Army way to build a latrine. I know that not only from the experience of seeing and using several latrines, but I’ve also read the manual.

Yep, the Army had a manual on how to build and operate latrines in the field. And for some reason I read that manual.

After arriving on the firebase, I remember asking one of my new FDC friends where the bathroom was and he pointed at a building and said I could use the Vietnamese latrine or … then he pointed to an open spot near the edge of the firebase and said, “Or you can use that.”

The only thing visible where he was pointing was a toilet. A single, white, porcelain toilet. It was out in the open with a beautiful view of the valley below us.

No building. No walls. No privacy.

Just a toilet.

We shared the hill with a Vietnamese unit and on the outside their latrine was like the others I had seen in Vietnam. It was a nice building. The thought of sitting out in the open while going to the bathroom did not appeal to me, so I decided to check out the Vietnamese latrine.

I opened the door and went into the building. It was small but very clean. It looked like they may have even modeled it after the American latrines.

Except for one thing.

There was no toilet.

There was a plastic floor mat where you could place your feet and there was a hole in that plastic floor mat where I figured you were supposed to do whatever it was that you came in the latrine to do.

I would later learn that out in the field where the farmers worked, it was fairly normal to see someone drop their pants, do their business, pull up their pants, and go back to work.

I had not, however, accustomed myself to the culture and decided to pass on the experience.

I decided to use the white porcelain thing sitting out in the open.

Trust me, it was a strange feeling to sit on a toilet in the middle of the night in clear view of anyone who might be out there in the darkness.

For some reason, I didn’t really enjoy the beautiful view of the countryside.

Other things were on my mind.

I was sure the firebase would come under attack while I was sitting on my shiny, white porcelain thing. I was sure mortars would explode around me, sappers would crawl through the wires with satchel charges, or a sniper had me in his sights right at the moment and thought it would be fun to take out the American soldier sitting on the toilet.

But what choice did I have?

I couldn’t do the squatting thing. I mean that was weird. I just couldn’t do it.

Until one day … the rains came.

It wasn’t the monsoon rains. Those would come later. This was just your ordinary torrential downpour.

As much as I didn’t want to use the Vietnamese latrine, I couldn’t imagine sitting out in the open during the downpour.

So … I decided to appropriate the culture of the Vietnamese soldiers and used their version of a latrine.

I was a little awkward at first but I was dry and after a few more uses of the latrine, I never went back out to the toilet in the open, even after the sun came out.

That’s enough latrine talk.

Sorry for bringing it up but, like I said, it was a memorable experience for me.

I’ll share more about life on a firebase in future episodes.

LESSONS

Never forget you are in a war. It may not be a physical war like I experienced in Vietnam, but it is a very real war for your soul. Choose to follow Jesus and know that there is a very real enemy out there who wants to destroy you.

Sometimes we are so used to our way of doing things (personal comfort) that we don’t even consider that another way may be a better choice.

Share this post