For those of you who would prefer to listen to the podcast, just click the player above. For the rest of you, keep reading.

Greetings from the Big Sky Country.

I was driving down the street yesterday and saw a sign posted on the corner. You know, the kind of sign that advertises a garage sale or an open house.

Only this sign did not advertise a garage sale or an open house.

This sign let me know that this coming weekend there is going to be a Reptile Expo in town.

A Reptile Expo.

What in the world is a Reptile Expo?

I’ve never heard of a Reptile Expo.

Do people show off their pet lizards?

Do wranglers — this is Montana, remember — do wranglers bring in a herd of turtles?

Will a group of mad scientists who play with DNA from ancient critters plan to show off a baby Tyrannosaurus Rex?

I have no idea what a Reptile Expo is, but it’s going to be here this weekend.

For those of you who don’t live in the Big Sky Country, I’m so sorry for you.

We have a Reptile Expo.

You don’t.

Today I’d like to take you on a trip into the past.

What can I say?

I’m a history teacher.

I love taking trips into the past.

CALEXICO, CALIFORNIA

This particular trip began a little over one hundred years ago in the small town of Calexico, California. The town was situated on the border with Mexico and had just over 6,000 inhabitants at the time our story begins.

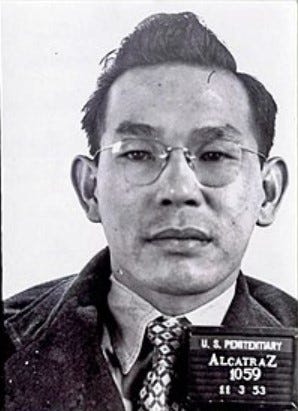

On September 26, 1921, Tomoya Kawakita was born. His parents were Japanese citizens, but being born in the United States, Tomoya automatically became an American citizen.

He grew up and went to school in Calexico. He graduated from high school in 1939 and then decided to go to college in Japan, his parents’ home country. He declared his allegiance to the United States when he picked up his U.S. passport and headed off to Japan.

IN JAPAN

Less than two years later, on December 7, 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and the world changed. Japan and the United States were now at war.

Tomoya was placed in what some may have considered an awkward situation. He could not return to the United States, and life could have been difficult for him as an American citizen in Japan.

But a family friend helped him get a job as a translator at a mining and metal processing plant. They needed a translator because many of the workers at the mine were prisoners of war forced to further Japan’s war effort.

Over the next several years, Tomoya earned a reputation among the prisoners as one of the most ruthless Japanese authorities in the mine.

After the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, Japan surrendered, bringing an end to World War II.

RETURNS “HOME”

Tomoya went to the American officials running Japan and requested a passport to return to the United States. He claimed he had never given up his citizenship but had worked for the Japanese under duress. He repeated his oath of allegiance to the United States and was given the passport.

When he returned to the United States, he enrolled at the University of Southern California, and tried to return to his old life.

In 1946, while shopping at a Sears store in downtown L.A., William L. Bruce, a former POW recognized Tomoya and followed him out of the store. Bruce wrote down the license number of Tomoya’s car and gave the information to the FBI.

The FBI arrested Tomoya Kawakita and the government charged him with 15 counts of treason.

THE TRIAL

The government did not lack of witnesses. Almost 100 former prisoners were willing to testify about Tomoya’s brutal treatment of the soldiers. The government only used about 30 of those men to make their case.

Tomoya’s lawyer argued that his client couldn’t have committed treason, because he had given up his American citizenship and become a Japanese citizen.

The prosecution argued that Kawikita had not officially given up his citizenship and even claimed when he requested a passport to return to America, he indicated he had not renounced his citizenship.

When both sides had finished their arguments, Judge Mathes, explained to the jury that they were not deciding if Kawakita had committed war crimes. The evidence was very clear that he had. The charge of treason, however, could only be proved if he was still an American citizen during his time in Japan.

The deliberations took several days. Three times the jury told the judge they could not reach a unanimous verdict on the charges of treason.

Each time, the judge told them to keep trying.

Finally, on September 2, 1948, the jury gave their verdict.

Tomoya Kawakita was guilty of 8 counts of treason.

Now it was up to the judge to decide the punishment.

Before announcing the punishment, Judge Mathes made a point of telling Kawakita of the many American soldiers who came from similar backgrounds — having parents who were Japanese nationals but who were also American citizens because they had been born in the United States — served bravely during the War and the judge also referred to the hundreds who had given their lives for the land of their birth — America.

Then the judge said …

“Throughout history treason has always been the crime most abhorred by English-speaking peoples. The traitor has always been considered even worse than a murderer. And the distinction is based upon reason: for the murderer violates at most only a few, while the traitor violates all the members of his society, all the members of the group to which he owes his allegiance.”

Judge Mathes

Judge Mathes ordered Kawakita to be executed.

Kawakita’s mother broke down when the verdict was announced, and Tomoya begged her not to kill herself.

THE APPEALS

Kawakita was now on death row.

His legal team immediately began the process of appealing the decision.

The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals1 reviewed the case and on June 22, 1951, the three-judge panel unanimously upheld the District Court’s decision.

Then the U.S. Supreme Court2 reviewed his case, and on June 2, 1952, decided by a 4-3 vote that Kawakita was indeed guilty of treason and execution was a reasonable punishment.

Tomoya Kawakita’s appeals were used up.

REQUEST FOR A PARDON

Many post-war leaders in Japan asked President Dwight Eisenhower to intervene in the case and pardon Kawakita.

The constitution gives the President a broad range of options concerning people convicted of federal crimes.

The President can pardon an individual, commute a sentence, lessen a punishment, or let the legal system work out without his intervention.

What would you do?

If you’re listening to the audio podcast, I would encourage you to pause it for a few minutes and consider what you would have done, if you had the power that President Eisenhower had.

If you’re reading this episode, just stop for a minute and decide what you would have done.

Then continue reading.

President Eisenhower Decides

After dozens of requests for a pardon for Kawakita, a report from the Attorney General, and a report from the Board of Parole, President Eisenhower issued his decision.

On October 29, 1953, President Dwight Eisenhower commuted the death sentence to life in prison.

Kawakita was removed from death row.

A number of people were upset with the decision because they felt Kawakita deserved to be executed for his crimes.

Others believed life in prison was an appropriate punishment.

President Kennedy Decides

But the requests for a pardon continued to come in.

John F. Kennedy, the President after Eisenhower, received many requests from Kawakita’s family members and from highly ranked officials of the Japanese government, to pardon Kawakita.

In 1963, in one of his last official acts before he was assassinated, President Kennedy issued a pardon to Tomoya Kawakita on the condition that he leave the United States and never return.

Kawakita was released from prison, went to Japan, and would pass away sometime in the 1990’s.

Justice is important to God.

Was justice done in this case?

What would you have decided?

Before I go, I’d like to share a blessing with you from the Old Testament.

“May the Lord bless and protect you; may the Lord’s face radiate with joy because of you; may he be gracious to you, show you his favor, and give you his peace.”

Numbers 6:24-26 (The Living Bible)

Until next time … be the reason someone smiles today!

Clint

United States v. Tomoya Kawakita, 96 F. Supp. 824 (S.D. Cal. 1951) :: Justia

KAWAKITA v. UNITED STATES, 343 U.S. 717 (1952) | FindLaw

Share this post